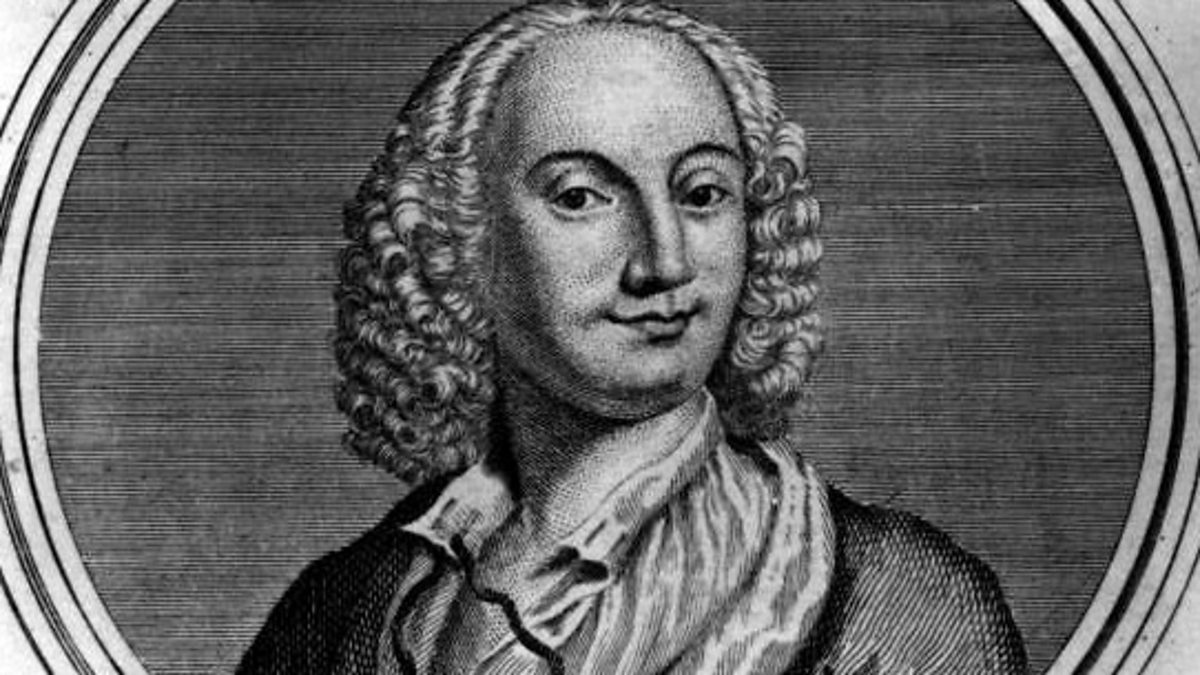

After the advent of cut and splice technology – and its use in the productions of CD recordings – lovers of classical music can be led to believe that every performance should be perfect, have no rough edges or loose ends. And yet “perfect” performances can be dry and lacking in human quality. In light of this, it was wonderful to hear La Serenissima give multi-dimensional, full-bodied performances in a concert celebrating one of the most human composers of all: Vivaldi.

- Adrian Chandler Four Seasons Cast

- Adrian Chandler Four Seasons

- Adrian Chandler Four Seasons Movie

- Adrian Chandler Four Seasons Family

- Adrian Chandler Four Seasons Tour

Vivaldi: The Four Seasons - La Serenissima/Adrian Chandler. The Four Seasons - Spring in E Major, RV. Drivers seewo information laptops & desktops. Drive Featured Album, from 28 September 2015 after 6pm.

- Adrian Lewis Peterson (born March 21, 1985) is an American football running back who is a free agent. He played college football at Oklahoma, where he set the freshman rushing record with 1,925 yards during the 2004 season.

- The Four Seasons-Spring In E Major, Rv. The Four Seasons-Spring In E Major, Rv. Adrian Chandler. Adrian Chandler. The Four Seasons, Concerto No. 2 in G Minor, RV 315 'Summer': I. Allegro non molto. The Four Seasons, Concerto No.

The first half of the concert was comprised of four different Vivaldi concerti: two violino “in tromba marina” concerti were alternated with two bassoon concerti. The violino “in tromba marina” gave the evening’s start a certain novelty. Both the instrument’s colourful history and unique buzzing timbre accrued a high level of interest from the audience. Unfortunately these two concerti were the weakest in the evening: both items had problems with ensemble and balance. In sections of reduced instrumentation the violino in tromba marina struggled to hold the centre of attention against the continuo team.

In addition to this, Adrian Chandler’s sound quality and intonation suffered at times, although this could have been in part due to the temperamental nature of his instrument. As Chandler wryly remarked, there was a reason that this instrument hadn’t survived until the present day: the marina’s pegs went a little haywire between movements. Still he gave the works a lot of character; the perky up-bow staccatos in the D major concerto gave the second movement a cheekiness, and the final movements in both concerti had a roughness reminiscent of a rustic barn dance.

The two bassoon concerti provided us with a contrasting sound aesthetic to the two marina concerti. Peter Whelan demonstrated his ability to draw a variety of timbral colours from the Baroque bassoon, producing a solid oaky tone in the first concerto, and more a dulcet one in the second. The variety of sound colours used by Whelan brought forth the works’ latent expressive powers. The softer colours suited the arioso style of the second concerto, and the harder colours punched through the texture in the first. Expression was further heightened by Whelan’s use of rubato, which was employed at particularly dramatic cadences.

The bassoon seemed to fare better than the violino de tromba marina against the rest of the orchestra balance-wise. Delightful counter-melodies – such as the beautiful cello continuo lines – were allowed to come to the surface at just the right moments. The ensemble itself matched Whelan in colour and expression, executing sharp juxtapositions in mood cleanly and bursting into the tuttis with frenzied excitement.

It was clear that the second half of the concert was much better rehearsed than the first. Previous issues with ensemble and balance disappeared as Chandler led La Serenissima through an adrenaline-fueled interpretation of Vivaldi’s most famous work: The Four Seasons. The ensemble worked like a well-oiled machine, adapting quickly to Chandler’s wild and unpredictable fluctuations in tempo. Indeed Chandler took a great deal of liberty with rubato. These liberties however did not cheapen the music at all, far from it. Instead they heightened the performance, keeping the audience right on the last millimetre of their church pews.

Chandler's tone varied from honeyed sweetness to rough and biting. His improvised decorations of repeated sections and also his cadenzas were truly stunning in their liquid fluidity and at times their chromatic adventurousness. Faster passages – at the end of Summer and the perilous triplets at the beginning Spring – were not totally note-perfect, but this was made up for by Chandler’s spirit, fervour and originality.

Chandler’s fresh approach was reflected in the orchestra as well. In Summer's Presto they matched him in both commitment and technical ability. Real gems included the second movement of Autumn, where Vivaldi’s progressive harmonies were allowed to speak for themselves, and the harpsichordist was able to demonstrate his improvised realisations. The second movement of Winter was my highlight. Here the cellist and theorbo player gave beautiful arcs to the phrases; together they propelled the movement forward with constant semiquaver motion, giving it a clear sense direction and also giving Chandler’s improvised ornamentations an extremely strong musical foundation. It was a pleasure to see the cellist take as much delight in this aspect of the Manchester version of the score as the audience.

The audience was recompensed in full for the initially uneven standard of music-making. La Serenissima reminded us that a good performance is not necessarily a note-perfect one. A good performance is passionate, entertaining, and sometimes sacrifices fine details in favour of big dramatic gestures.

See full listingAdrian Chandler Four Seasons Cast

The Dawn of the Stradivarius: James Ehnes and La Serenissima in Oxford

Adrian Chandler Four Seasons

Vier Violinen und ein Mezzo: La Serenissima in der Wigmore HallAdrian Chandler Four Seasons Movie

Adrian Chandler Four Seasons Family

Adrian Chandler Four Seasons Tour

To add a comment, please sign in or registerMobile version